Tag: Visual edit |

No edit summary Tag: Visual edit |

||

| Line 17: | Line 17: | ||

• [[Image:Usflag tiny.png|24px]] |

• [[Image:Usflag tiny.png|24px]] |

||

United States (later, covert) |

United States (later, covert) |

||

| − | | combatant2 = |

+ | | combatant2 = Rebel Coalition: |

• [[Image:Lingang socialist flag tiny.png|24px]] |

• [[Image:Lingang socialist flag tiny.png|24px]] |

||

Socialist Party of Lingang |

Socialist Party of Lingang |

||

| Line 24: | Line 24: | ||

Bull Elephant Society |

Bull Elephant Society |

||

| − | • |

+ | •[[Image:Lingang democratic flag tiny2.png|24px]] |

Republican Democracy Party |

Republican Democracy Party |

||

| Line 41: | Line 41: | ||

• [[Image:Bullelephant flag tiny.png|24px]]Bull Elephant Society: ~201,573 (est.) |

• [[Image:Bullelephant flag tiny.png|24px]]Bull Elephant Society: ~201,573 (est.) |

||

| − | • [[Image:Lingang democratic flag |

+ | • [[Image:Lingang democratic flag tiny2.png|24px]] |

Republican Democracy Party: 55,870 |

Republican Democracy Party: 55,870 |

||

| Line 48: | Line 48: | ||

| casualties1 = [[Image:Lingang flag tiny.png|24px]] Lingang: |

| casualties1 = [[Image:Lingang flag tiny.png|24px]] Lingang: |

||

<br>400,322 dead<br>600,243+ wounded<br>Civilian casualties<br>52,977 dead |

<br>400,322 dead<br>600,243+ wounded<br>Civilian casualties<br>52,977 dead |

||

| − | | casualties2 = • [[Image:Lingang socialist flag tiny.png|24px]] |

+ | | casualties2 = • [[Image:Lingang socialist flag tiny.png|24px]] Rebel Coalition: <br>734,200 dead<br> 150,000 wounded<br>99,000+ missing<br>Civilian casualties: unknown |

| notes = |

| notes = |

||

}} |

}} |

||

Revision as of 02:24, 23 August 2021

The Red Revolution (also called the Bloody Decade or the Linganese Democratic Revolution) was a period of social and political upheaval in Lingang, which began with a popular uprising in Ashetowne, in the state of Aurendale in 1964, and escalated into a civil war that lasted until 1975. Much of the war was a devastating stalemate until the introduction of SB-113's, then referred to as "Welburg’s Metal Men," very quickly helped turn the tide of the war in the favor of the Linganese Federal Government. The revolution, though failed, had a lasting and profound impact on Linganese politics and society.

Aerial photo of protests and rioting during the Ashetowne.

Ashetowne Uprising

In 1964, during what became known as the Ashetowne Massacre, the Linganese Police, armed with assault rifles, began firing on rioters and crowds of anti-government demonstrators, who had gathered in response to the growing pro-democratic movement that had begun to take hold among the populace. They were largely inspired by images of social changes and revolutions abroad, especially the American Civil Rights Movement, so much to the point that slogans and protesting styles were taken from the American movement. The killing of demonstrators sparked widespread outrage as the images were broadcast nationwide. Various other protests and demonstrations began to spread across major urban areas and were met with increasing force from federal and local authorities. In turn, protestors took to looting and arson, and began to fight back with whatever tools were at their disposal. Though better equipped and armed, police forces across the nation became overwhelmed, and so local leaders called on the federal government for assistance.

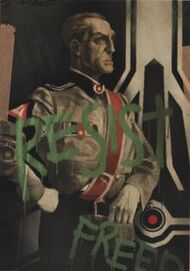

A propaganda poster of Lord Welburg defaced with rebellious slogans, 1966.

The situation further escalated when on 28 October of that year, Supreme Lord Tyrus Welburg announced a national military campaign to end the uprisings. He made a rare televised address to the nation, famously declaring, "The violence will cease. The so-called 'Social Movement' will end. Democracy dies today." The brutal crackdowns involved civilians enduring curfews, prolonged detainment, summary and public executions, and the persecution of individuals thought to be connected with the pro-democracy movement. One such individual, Nicholas Levine, already a well-known leftist and pro-democracy advocate who mutinied from the army, was a prime target but managed to escape capture. Levine would go on to become a prominent figure in the Socialist Party of Lingang for the duration of the revolution.

Second Civil War & Levine's influence

It was around March 1965 that the rebellions began to show some level of serious organization. The illicit Socialist Party, led by Levine, openly stated its goal to replace the authoritarian federal government with a democratic society based on a mix of communist ideals. Levine's party would garner the attention and approval of anti-statists and anarchists as well, including Denise Cha'gaguea, a native Linganese far-left activist. The inclusion and visibility of Cha'gaguea in the uprisings sparked greater activism and unrest within the already angry Native populations of Lingang, who collectively had been oppressed ever since Europeans first colonized the continent. Smaller Native-led rebel groups would arise during the revolution, however most flocked to the Socialist Party and Bull Elephant Society, the latter of which was an anarcho-socialist militant group that took its name from rebels during the First Linganese Civil War of the 19th century.

Flag of the Socialist Party of Lingang

The hardline actions and brutal oppression of the civilian population took its toll on some members of the Linganese Army, and several bands and regiments mutinied during the later half of 1965 and 1966, providing much needed arms, experience, and training to the various rebelling factions that had arisen in the summer of that year. The extra arms meant that the Socialists and other rebels had the means to properly defend themselves against the rest of the Armed Forces, and prolonged fighting took place in the ensuing years. The urban warfare was particularly brutal. A notable bombing run was conducted against the city of Maurentide on 2 April 1967, which had been taken by rebels some months prior. The bombings killed thousands and left the city in ruins. Maurentide was of great importance to the Socialist Party as it was a major producer of weapons and goods, on top of the massive humanitarian crisis that followed. The bombing is largely seen as having shaped the world's perception of the conflict.

News of the widespread slaughter spread worldwide and was extensively covered in media. The United Nations released a statement condemning Lord Welburg's regime, the first such condemnation, and demanded that the Linganese Armed Forces cease the atrocities against non-combatant civilians. Preparations for peace talks were also made, but none were ever fruitful. The United States publicly condemned the Federation's military actions, however there were concerns among American intelligence and military circles about a possible communist victory in Lingang. Disturbed by the idea of a large communist neighbor in the South Pacific, President Lyndon B. Johnson privately mused about direct involvement, but ultimately did not militarily intervene, as the US was already fighting the Vietnam War. The Soviet Union expressed solid support for the Socialist Party and other left wing rebels, and provided some aid to the factions in the form of training, intelligence, and shipments of weapons and other tools, but did not commit to sending troops.

Turning Tides

By 1970 the fighting had been reduced to a bitter stalemate between Federal forces and Communist rebels. Federal troops were having trouble adapting to the brutal guerilla tactics of the Rebellion, leading to a high number of casualties and soldiers either missing or wounded. Nicholas Levine made several pleas and attempts to secure Soviet military support in the form of troops, but Soviet leadership refused to get the USSR further involved in the Linganese war, fearing greater escalation of the Cold War with the U.S. However, a greater amount of weapons and ammunitions were supplied to left-wing rebels in the period from 1970 until the end of the war. Supreme Lord Welburg, also weary from war, turned to his engineers and scientists to come up with a quick solution to end the crisis. They began a project to create better tanks to withstand rebel fire and to be immune to chemical gas. The project eventually came up with designs for tall, bipedal tanks, unofficially referred to as "Welburg's Metal Men," that would later be deployed during the final years of the war.

With the Vietnam War drawing to a close, the US began to devote greater attention to the Linganese conflict, albeit in secret. There are still some records which show that CIA operatives met directly to advise Linganese military leaders, and provided weapons and aid to federal forces. It is also widely speculated that the CIA had much to do with the invention of Welburg's Metal Men in the first place, however both the US and the Dictatorial Federation dispute these claims. By late July they were ready for deployment. Unaware of these secret plans, rebel forces had mobilized for a second, more careful assault on Strautenburg. However they were greeted by the sight of the Metal Men towering above the ruined buildings of the capitals outer boroughs, waiting for them. The Second Battle of Strautenburg was in all actuality a massacre of rebel forces, who had not prepared for, nor could conceive, such machines at the command of the Federals. Agile and powerful, the Metal Men marched forward with scant resistance from the rebels, who were mowed down in droves. Such a shocking turn of events led thousands of rebel soldiers to simply retreat or desert, but many more lost their lives to the Metal Men. Few escaped the carnage, including Levine, miraculously, who managed to escape to a rebel stronghold in the Western Desert.

Image taken of prototype SB-113's from the Federal Recapture of New Victoria City. Countless civillians perished during the final few years of the war.

With the tide of the war turned, the imposingly tall yet agile Metal Men wrought utter destruction and havoc upon rebel held cities and towns. Civilians, many of whom were never combatants in the war, were slaughtered indiscriminately whenever and wherever they were caught in the paths of the Federal war machines. Most rebel forces along the eastern seaboard quickly surrendered upon the arrival of the Linganese Army accompanied by the death machines, though some were not provided the chance. Word of this new spate of massacres at the hands of the Linganese Armed Forces was met with indignation and disbelief, however little was done to stop it aside from stern condemnations and economic sanctions. A full scale invasion of the island-continent of Mu was both impractical and politically risky, and so the world was forced to watch as the last of the Socialist and pro-democracy movement in Lingang was being crushed underneath an iron boot.

War's End and Aftermath

One of the few surviving photos taken during the Blackout Years. The grainy, low quality image depicts what is possibly Lord Welburg addressing a large audience.

By early winter of 1975 the last of the rebel strongholds had been mostly recaptured. On 9 February of 1975, Nicholas Levine and other prominent rebel leaders who had managed to evade Federal Forces were found in a compound on the outskirts of the city of Salvadale. Their surrender and capture heralded the capitulation of any remaining resistance left within Lingang, effectively ending the Second Civil War. Levine and all rebel leaders who had been found were taken to Strautenburg to be put on trial. They were all found guilty of treason, sediton, and various crimes against the state. With an audience of beleaguered citizens and loyalists compelled to witness, the rebel leaders were tortured to death upon a large stage in front of the crowd, with Levine being tortured and then disemboweled last. His head was left upon a pole in the city square. Though most rebel leaders had been killed, Denise Cha'gaguea and some anarchist activists did manage to flee Lingang some weeks prior to the end of the war, and sought asylum in Moscow. What happened to her afterwards is unknown, though in a departing letter she had written, Cha'gaguea regretted the failure of the rebellion and lamented that “Lingang’s spirit and dream of freedom simply vanished into thin air.”

With much of the nation torn asunder and large swathes of infrastructure in ruins, the exhausted people of Lingang put up virtually no fight against the victorious Federal Government. Quickly, Lord Welburg set to the task of rebuilding the broken nation to his liking. In the summer of 1975, faced with economic sanctions, Welburg's government enacted a policy of autarky that initially led to widespread shortages and hunger. Despite this, determined to prevent any sort of uprising in the near future, Lord Welburg pushed on and began Operation Homeland, a nationwide program that sought to rebuild Linganese society from the ground up. By his orders, all television and radio stations were to cease operations, and all contact with any media or information sources outside of Lingang was strictly forbidden. Future television, radio, and later internet providers would be entirely contained within Lingang, and could only be fed information by the new Department of Communication and Intelligence (DCI). The narrative of Lingang's history was radically restructured to fit within the National Party's accepted teachings. Any person who dared to dissent was quickly removed, their records expunged, and were never heard of again. Operation Homeland lasted until late 1990, when Lord Welburg declared the mission of rebuilding the nation "a total success." The period from 1975 until the end of the operation in 1990 is, quite appropriately, known as the Blackout Years due to there being such little information about the internal operations of Lingang during that time. Very little photos or records exist, or at least very little have managed to escape Lingang. The information that is present suggests that mass numbers of citizens were detained in camps, murdered by state police, or otherwise subjected to "experiments" and other horrors by the state, all apparently kept secret. It is widely speculated, and highly likely, that periodic outbursts of unrest and rebellion still occurred amongst the populace during this time. However, with no serious coordination, and heavily outnumbered and outgunned, no such revolts were able to succeed. There are some reports that a low-intensity insurgency persists to this day, though is mostly confined to the Western Desert.

Though it failed, the Red Revolution was nonetheless a profound event that changed the course of Linganese history forever. Through the revolution's demise, the Linganese state machine was able to become far more ruthless and controlling than it ever had been before. It is unknown how Lingang would have looked had the revolution succeeded, or whether true democracy and freedom would've ever occurred in its wake. However, it is very clear to us that whatever may have happened, it would have been infinitely better than what did happen after the failure of the revolution.